Four Views of Pompeii (2004)

for string quartet and harp, 18 minutes

Instrumentation

string quartet (2 vn, va, vc), harp

also in a piano version

Recording

A Fiery and Still Night, Capstone (2006)

Inspired by ancient Roman wall painting, each of the four movements evokes a distinct style of “Pompeian” painting. Premiered by the Cedar Rapids Symphony Chamber Players in 2004.

Movements

I. Vast Airy Mansions (2nd Style)

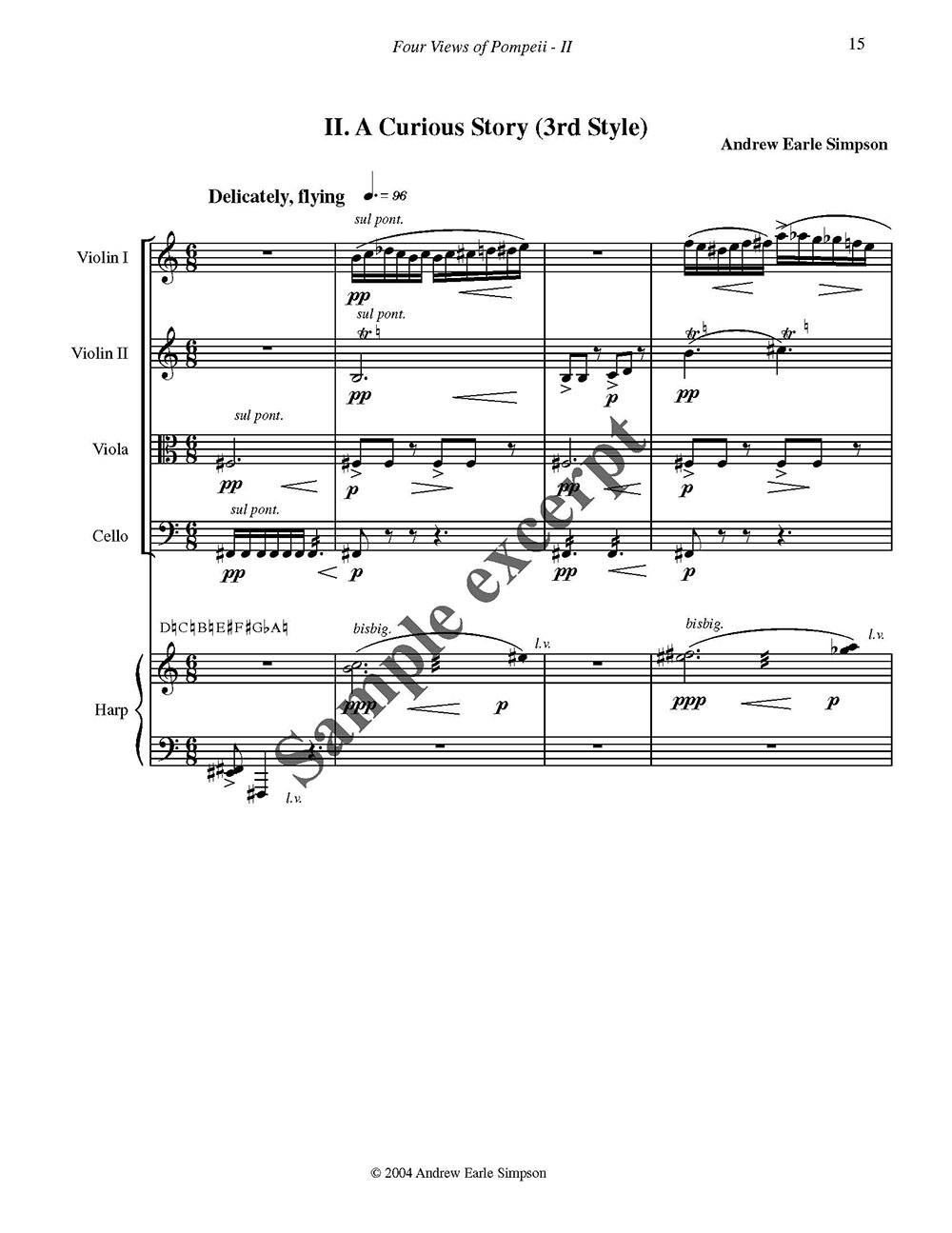

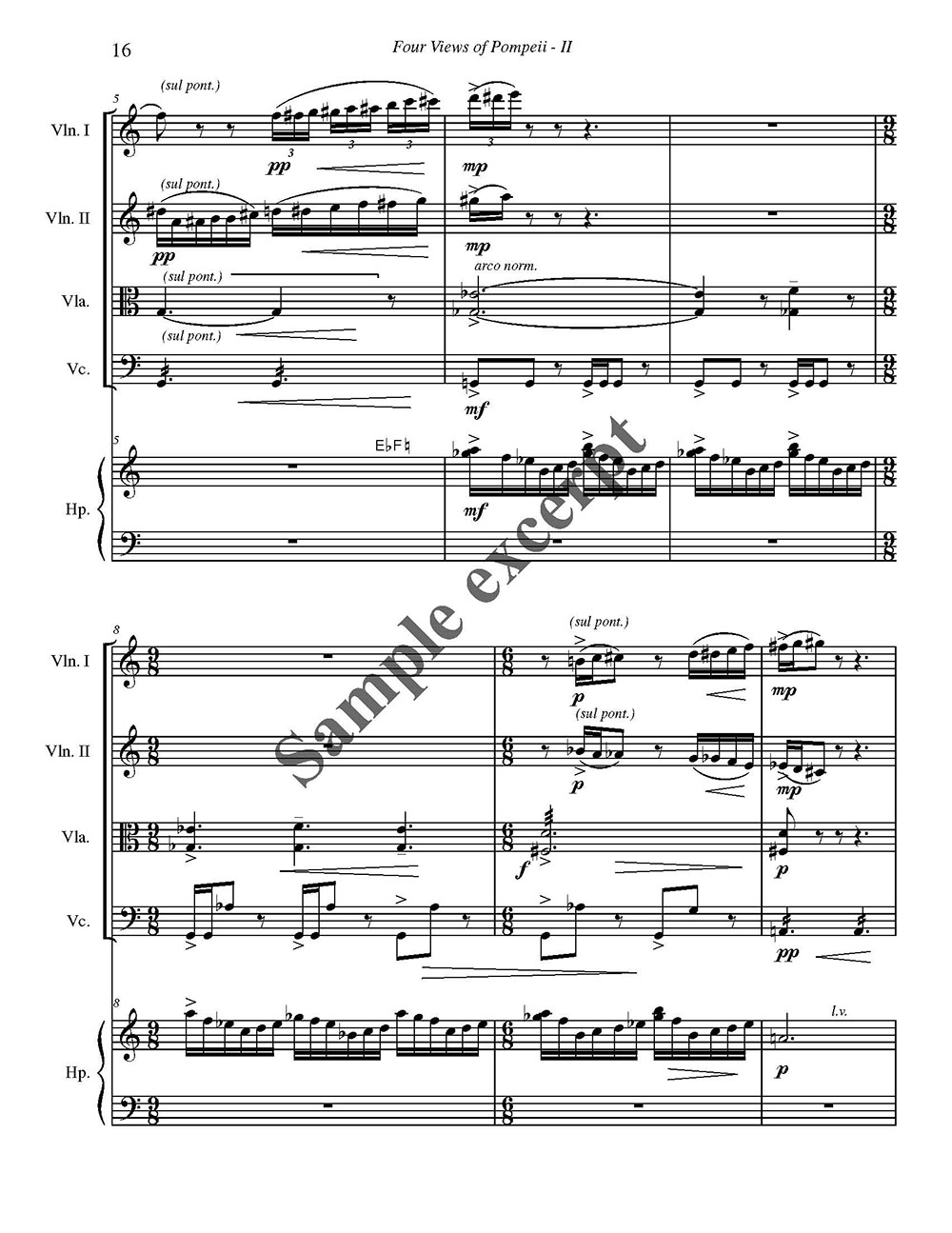

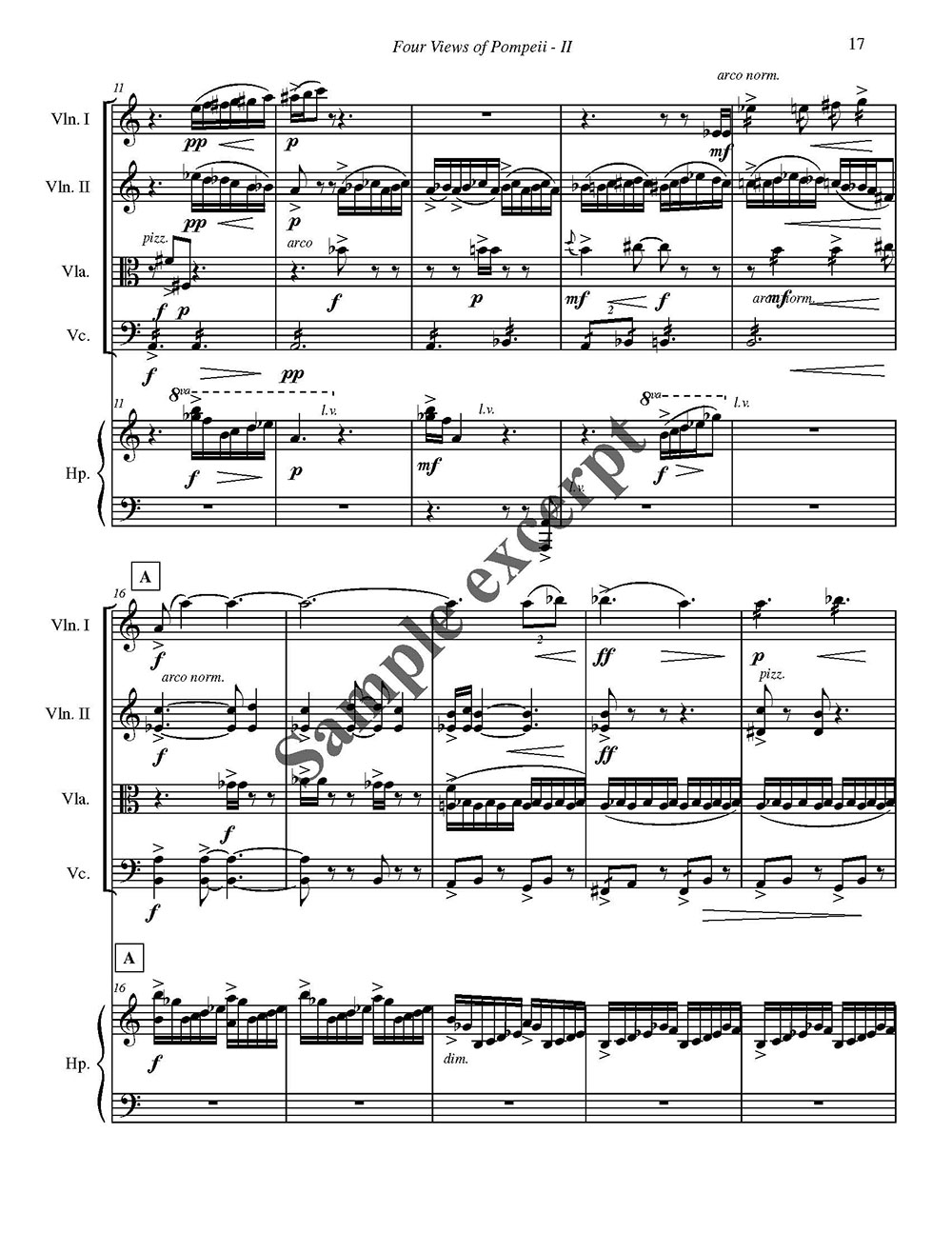

II. A Curious Story (3rd Style)

III. Polychrome Elegy (1st Style)

IV. Nero and the Golden House (4th Style)

Listen

A Curious Story (excerpt)

Polychrome Elegy (excerpt)

Nero and the Golden House (excerpt)

Program Notes

Four Views of Pompeii, for string quartet and harp, is the second of two chamber works commissioned as part of the “Museums, Composers, and Communities” residency sponsored by the American Composers Forum and the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art (CRMA), as part of the museum’s exhibition “Art in Roman Life – Villa to Grave.”

As resident composer for this exhibition, I have composed two new chamber works inspired by the “Art in Roman Life” exhibition for professional performers based in the Cedar Rapids vicinity. The Red Cedar Trio premiered the first work, Tesserae, at the CRMA in April 2004. The Cedar Rapids Symphony Chamber Players presented the World Premiere of the second piece, Four Views of Pompeii.

Background: Roman Wall Painting

Whereas Tesserae dealt principally with selected ancient Roman busts from the CRMA’s Riley collection, the subject matter of Four Views of Pompeii is ancient Roman wall painting, a very important and difficult area of archeological and artistic research.

The four styles of wall painting were codified in the late 19th century, based on study of the numerous surviving wall paintings from Pompeii, buried beneath the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 AD. Although the four styles of painting are often associated with Pompeii, they are typical of painting throughout the ancient Roman world.

The four styles of wall painting are listed in chronological order, with First Style being the earliest. Here is a brief, and by no means exhaustive, non-specialist description of the four styles:

First Style – the dates of origin are uncertain; however, it appears to have been in existence since the 2nd century BC or sooner. First Style paintings consist of large colored blocks painted to resemble masonry, often with a faux marble appearance.

Second Style – beginning early in the 1st century BC, this style includes illusionistic, trompe l’oeil architectural features used to lend depth or perspective to rooms. Often, paintings in this style are quite elaborate and fanciful, creating entire cityscapes or receding colonnades.

Third Style – roughly from 15 BC-50 AD, a principal feature of this style involves small painted scenes centered within a larger, plainer panel. The inset medallions or pictures are often quite intricate and elaborate on a very small scale, in contrast to the much larger scope of the Second Style.

Fourth Style – the latest of the four styles, from 50 AD to about the 2nd century AD, features extremely colorful and vivid scenes, often with mythological or heroic subjects.

Composing Four Views of Pompeii

As a composer with a strong visual sense, I searched for elements of each of the four styles of painting which suggested musical analogues, and then composed four movements – one per style – as musical “depictions” of them. In each movement, a specific work of art provided inspiration. The title of this work is something of a misnomer, by the way, as not all of the wall paintings inspiring this piece were actually found in Pompeii. However, as previously mentioned, these styles of painting generally apply throughout the Roman world.

The four movements are presented not chronologically by painting style, but in the most musically satisfactory order.

The first movement, titled “Vast Airy Mansions,” is based on the Second Style. Because the second style of painting involved visual illusion, I sought to employ methods of musical illusion. Music lends itself very well to trompe l’oreille (“trick the ear”) effects, and is an excellent analogue to illusionistic painting. Here are some examples of musical illusions employed in the movement:

Register (high and low) – strings and harp play “harmonics,” high, crystalline tones which greatly extend the range of the instrument.

Instrumental “identity” – near the end of the movement, the cello plays very high in its range, and the viola plays very low, allowing them to sound like each other, to “change places,” in effect. At another point, the two violins share one line, alternating with each other very quickly to give the illusion of only one player playing the line.

Rhythm – the simple melody heard at the beginning of the movement is sometimes heard at a different place in the measure, although sounding as before.

Another illusion involves a continuous upward or downward “slide,” or glissando. The viola, cello, and harp take turns playing these glissandi in such a way that the illusion of a continuously rising (or, later, falling) line is created.

A simple melody is presented by the first violin at the beginning: the melody returns throughout this first movement, but is often subjected to special treatment.

“A Curious Story” is the title of the second movement, based on the Third Style of painting. Underlying soft drones represent the large wall panels; elaborate filigree patterns played by small groups of instruments represent the small inset pictures. The glassy sound often heard is an effect called sul ponticello, in which players are asked to bow on the bridge, an unusual part of the instrument. There are three distinct themes which appear during the movement: one martial, one amorous, and one conniving. These themes interact with each other, are sometimes heard together, and then suddenly disappear, just as might be seen in a room with various small painted scenes. Do the themes tell a story? What is the story? No clear picture is given, and the movement offers no conclusions.

This title is also a tribute to Robert Schumann, the great 19th-century German composer who also drew musical inspiration from extra-musical things. The second movement of his piano work, Scenes from Childhood - a great personal favorite - is also titled “A Curious Story.”

“Polychrome Elegy,” based on the First Style, is a lyrical slow movement. The large interlocking blocks of masonry are represented by four overlapping chords played by the bowed strings. Each chord represents a distinct “color,” although the color of the chords is a purely personal association (many musicians associate specific pitches or keys with colors, making an interesting connection between visual and aural art). Therein lies the “polychrome” aspect of the title.

Because overlapping chords are not sufficiently interesting in themselves, however, the viola enters with a long-breathed melody, later taken up by first violin and cello. This melody serves as the principal musical focus of the movement. Short rhythmic patterns, with unusual sounds, are heard at two points in the movement. This is an effect calling for the players to play the instruments with the wood of the bow rather than the hair.

Elegy is an ancient Greek form of poetry adopted by Roman poets; to modern readers, elegies are thought of as funeral or melancholy poetry, although this does not necessarily define their original sense. Although not all ancient Roman poetry was intended to be sung, the poems which we read today were often first heard in sung form.

“Nero and the Golden House,” the finale, is based on the Fourth Style of painting, contemporary with the Emperor Nero (reigned 54-68 AD). The “Golden House” is his Domus Aurea, the Emperor’s massive personal palace built in Rome after the great fire which consumed much of the city. The Golden House, in fact, contains many examples of Fourth Style painting.

Several disparate elements contributed to the nature of this finale. First, taking my cue from the often elaborate and extravagant nature of Fourth Style painting, the final movement is highly extroverted in character. Second, Nero was himself a musician (it is probable that he did indeed possess genuine talent) and avidly desired to excel, and to be acclaimed, as a performer. He organized a grand circuit of musical competitions throughout Italy and Greece and – incredibly! – was declared the winner of every competition he entered. The image of a young, wealthy prima donna emperor as a star musical performer resonates in the contemporary mind as: rock star, lead guitarist. Finally, the image of Nero “fiddling while Rome burned” is well known to all, although the fiddle as such was not known to the Romans.

Chamber music is often thought of as a democracy, or conversation among equals. However, tyranny is a very different matter, wherein the give-and-take breaks down, and one party rules over all. In this final movement, the first violin engages in musical tyranny, taking on the persona of Nero.

Beginning with a deliberately long-winded and theatrical solo, the first violin is later joined by the full ensemble in a rhythmic, rock-like drive. The first violin takes another solo near the middle of the movement, as the other instruments play a repeated accompaniment figure. Contrasting sections of more gentle music show a more gentle aspect to Nero’s musicality: these sections are generally short-lived, overpowered by the more aggressive surrounding music.

The finale builds in intensity until the final bars, in which the first violin plays a figure which rhythmically matches Nero’s supposed final words, “Qualis artifex pereo!” – “What an artist is dying!”

—Andrew Earle Simpson